1914, just as 1900 had been, was a landmark year. Europe was in the throes of a war like it had never weathered before. For one thing, Europeans were not really sure what the fighting was all about and why they were at war in the first place. Furthermore, this was the first time that Europe had experienced industrialized warfare and death. Europe's reaction was to deny these realities and to proceed to sell this war to the young people in the terms of medieval chivalry: "For God, King, and Country." Little did Europe know that by the end of World War I more than eight million people will lose their lives in this "war to end all wars."

The realities of war

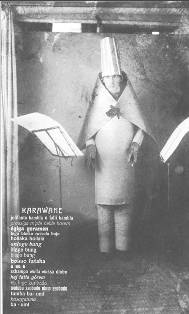

Nevertheless, the group coalesced and, under the leadership of Hugo Ball, a German conscientious objector, established the Cabaret Voltaire, a kind of "clubhouse"-café that could seat 50 patrons and where artists could perform their music and poetry as well as exhibit their works of art. The Cabaret Voltaire was the kind of place where people went to chat, drink, dance, and be outrageous. It became, in fact, a place where one could find refuge from the horrors of war and conventional life by embracing activities and objects in opposition to Western culture. The audience could hear Hugo Ball or other musicians playing conventional dance music, Satie's latest compositions, or bruitist music made with such unmusical instruments as a vacuum cleaner. On a given night the entertainment might have consisted of poets reading poetry consisting of words selected in random sequence, sound poems composed of meaningless syllables, or "simultaneous poems" made up of two or more poems declaimed concurrently. Sometimes, the audience was even treated to performances by several chorus members who donned child-like masks while they moved around like marionettes.

Hugo Ball

Amongst the members of the Zurich Dada movement were Marcel Janco, Tristan Tzara, Jean Arp, and Richard Hulsenbeck. Their aim was to found an international movement in art and literature that used ridicule and nonsense to reflect what was considered the meaninglessness of the modern world. In other words, their common bond was their distrust of civilization and their intention of challenging the traditional notions of art. As a consequence, the Dadaists forged ahead to create a new artistic vocabulary and language that would protest the horrors of World War I and condemn Western culture for its moral corruptness in accepting and propagating this war. The Dadaist's rallying cry in the wilderness became regressing into the innocence of childhood, with the hope of wiping the slate clean and launching a new culture from scratch. With this mission in mind, by 1917 the Dadaists had established a gallery and were publishing a journal.

At first, the Dadaists used shock, provocation, and irrationality as a weapon against the culture that condoned the industrialized murder taking place. They became artistic anarchists who poked fun of the "seriousness", formality, and sanctity of traditional art. Their solution was to purge Western culture and replace it with a new "elementary", child-like art that would save mankind from itself. This new art was to be toy-like, anonymous, collective, and born out of spontaneity, chance, and provocation. Jean Arp created wood-reliefs of bright, free-flowing shapes that simplified the appearance of natural things. Sometimes Arp would concoct art by standing above a canvas and randomly dropping on it squares of torn, colored paper that were then glued on at the point of contact. Arp also used coincidences of sound to reveal connections between the most unconnected ideas, as in this poem:

The Guest Expulsed

Their rubber hammer strikes the sea

Down the black general so brave.

With silken braid they deck him out

As fifth wheel on the common grave.

All striped in yellow with the tides

They decorate his firmament.

The epaulettes they then construct

Of June July and wet cement.

With many limbs the portrait group

They lift on to the Dadadado;

They nail their A B seizures up;

Who numbers the compartments? They do.

They dye themselves with blue-bag then,

And go as rivers from the land,

With candied fruit along the stream,

An Oriflamme in every hand.

The Dadaists also wrote poetry by cutting newspaper articles up into tiny pieces, none of them longer than a word, putting the words in a bag, shaking them well, and allowing them to flutter on to a table. The arrangement in which they fell constituted a "poem" that revealed something of the mind and personality of the author.

The use of chance opened up an important new dimension in art: the techniques of free association, fragmentary trains of thought, unexpected juxtapositions of words and sounds. According to Jean Arp, "The law of chance, which embraces all other laws and is as unfathomable to us as the depths from which all life arises, can only be comprehended by complete surrender to the unconscious. I maintain that whoever submits to this law attains perfect life." Each Dadaist explored the nature of spontaneity and chance in his own way. Marcel Janco used any objects that life put in his way. He incorporated these objets trouvés, wire, thread, feathers, into his works of art. The use of chance had yet another purpose: to restore to the work of art its primeval magic power in an age of disbelief. For the Dadaists, this primeval magical power had to be restored because it had been destroyed by a culture that championed the use of reason above all. The Dadaist legacy was to reinstate the balance between reason and anti-reason, sense and nonsense, design and chance, consciousness and unconsciousness.

Collage (1917)

Mask (1920)

The Dadaists also balanced the seriousness with which they perceived the predicament of modern man with laughter. They took laughter seriously, becoming the expression of their contempt for the hypocrisy of the modern world. And so the Dadaists proceeded to ridicule everything through the creation of anti-art and thereby raising public hell and outraging public opinion. As soon as the Zurich public would develop an immunity to whatever was being attacked and ridiculed, the Dadaists thought of a new target for their derision.

There were other groups of artists in other parts of the world that, although they were unaware of one another, shared in their undermining of both war and art. When they finally became aware of each other, it was through the frail little magazines that each group put out. The painter Francis Picabia served as the catalyst for the encounters between these groups as he traveled by chance from city to city. Because of illness, Picabia had escaped from Paris' despair and inscription into the army through a medical discharge and traveled to Barcelona, where he rallied a group of refugee artists and published a magazine called 391. The most colorful of the members of the Barcelona Group was Arthur Cravan, who was not only a professional prize fighter but famous for his savage attacks on paintings and writings that had won large acclaim. Francis Picabia then went to New York where he came again into contact with his friends Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, the leaders of New York Dada.

Bicycle Wheel (1913)

Once Duchamp joined Picabia in New York, their madcap antics increased. In 1917, Duchamp declared war on the New York art world by playing a joke on them. The Society of Independent Artists had announced an art exhibition open to any artist who had six dollars to plunk down as an entry fee. Duchamp decided to test the sincerity of this group by sending in a porcelain urinal which he titled Fountain and signed "R. Mutt" along with the six dollar entry fee. The hanging committee refused to display it as sculpture. The art world would never be the same on account of all of the controversy that this test case generated. Duchamp proved that the critics were hypocrites who were not really interested in artistic freedom. This scandal only encouraged Duchamp, Man Ray, and Picabia to continue their artistic subversion, always pushing the limit of what they could get away with.

Fountain (1917)

But in 1918, Picabia was struck with a mental disorder and traveled to Switzerland to get medical help. In Zurich, Picabia was greeted with great fanfare, "Long live Picabia, the antipainter arrived from New York." By then the cross-pollenization between all of the Dada groups was complete. After the war, some of the Dadaists returned to Paris where the movement fizzled out because it had only meant to be a state of mind. By definition, true Dadas were supposed to be against Dada, but, ironically, they had become too comfortable with themselves. Like the phoenix, Dada went down in flames and was resurrected in the form of surrealism.

Some of the Zurich Dadaists, however, returned to Berlin after the war, and, although German Dada became allied with the political left, it, nevertheless, was as short-lived as Paris Dada. Perhaps the German Dadaist artist whose work is best remembered is Kurt Schwitters, the creator of merz. Schwitters created his art out of all the junk and refuse that modern society manufactured. He collected tickets, newsprint, buttons, rags, wire, and any discarded scraps that he was able to pick up and incorporated them into collages, paintings, and even environments. Perhaps his work was able to transcend the short-lived Dada movement because he took such great care in creating well-balanced compositions of great beauty.

Merz Picture 25 A (1920)

In the end, what did Dada accomplish in its very short life span? Did the Dadaists merely jolt the bourgeoisie through their zany behavior? There is no question that the Dadaists succeeded in destroying the already tattered remnants of aesthetic traditions that had become anachronistic and decadent. But other art movements had succeeded in doing the same thing. What distinguishes Dada is that it questioned the basic assumptions of all art and thus cleared the way to start from scratch.