Expressionism: A New Rebirth

By the last quarter of the nineteenth century, artists were already beginning to sense that Western art was becoming too staid. This awareness was perhaps triggered by the influence that critics and academics exerted on every facet of painting, for they had the authority to dictate the rules that were to be followed. Thus the critics became a kind of police that could censor artistic freedoms by limiting the range of subject matter, themes, colors and style. As a result of this artistic restraint, artists felt stymied, rebelled and took it upon themselves to question these artistic limitations and to strike in new directions. Frederick Nietzsche, a German philosopher, went a step further and insightfully analyzed the source of their discontent in a work that traced the development of ancient Greek drama and the complexity of the Greek vision of life.

In The Birth of Tragedy (1872), Nietzsche explores the Greek need for balance in everything. On the one hand, the Greeks worshiped Apollo, the sun god, who represented for them every trait that they associated with being cultured and civilized: restraint, harmony, decorum, creativity and rationality. And so, Apollo became for the Greeks the emblem of curtailing form, of living by the rules that society established so that it could function properly. However, the Greeks also paid homage to Dionysus, the god of wine. For the Greeks, this god was savagery incarnate, for he represented uncontrolled frenzy and primitive urges. In short, Dionysus was the symbol of wild, destructive pre-societal forces. How does Nietzsche explain this paradoxical worship of two gods that are so contrary to one another?

For the ancient Greeks, the gods represented human attitudes and states of mind. To have honored just one god would have been too limiting on the human personality, for the god would have appropriated the worshiped, rendering him or her with the traits associated with the god. Someone worshiping Apollo alone would surely suffer by becoming a too restrained individual. By contrast, a person sole honoring Dionysus would become wild and uncivilized. Besides, on a more literal level, one of the two gods would have become jealous of the other and would have decreed punishment. And so, in order to ensure that the wrath of any one god was not unleashed and that a worshiper's personality remained balanced, the Greeks worshiped all of the gods equally.

According to Nietzsche, the Greeks transferred onto the arts how they viewed and experienced life. They were so successful as artists, sculptors, architects, dramatists and poets because they understood that their creations had to adhere to the principle of balance just as they did in life. And so in trying to strike a balance, the Greeks synthesized the Apollonian and Dionysian forces within themselves and channeled them into their works of art. The Dionysian elements within them is the inspirational, chaotic passion from which creation springs; the Apollonian harnesses these wild strains into orderly form. As a consequence, the two antagonistic forces work together to create a work that wells out of passion but that is tempered by rationality.

Unfortunately, by the beginning of the twentieth century, this balance had been broken in Western art. By this time frame, art had been too bound by academic rules, lacking both verve and vitality. Apollo had become dominant strain. Modern artists at that time understood that if they were going to restore this balance, a new artistic rebirth akin to the Renaissance had to re-occur. Whereas during the Renaissance, artists had looked at the ancient Greeks and Romans for direction, at the beginning of the century they now looked to the primitive cultures of Africa, Asia and the Americas for an invigorating inspiration. What differentiated these two very different rebirths was that the Renaissance looked back for moderation and balance, but the new moderns felt that in order to bring about change they would have to imitate the abandonment, distortion, and excesses of primitive art as a means of restoring equilibrium in the future.

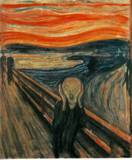

The Scream (1893)

Perhaps the first group of artists to come to these realizations were living in the city of Vienna and for a good reason. After all, Sigmund Freud was a resident of this city and was writing at this time about his discoveries on the nature of neurosis and its source, the repression of one's primitive urges. And so, it is only fitting that the artistic liberation from all of the restraints imposed by an overly civilized society which clung to traditions should take place in Vienna. The new group that was born out of this rebellion, the Secessionists, were driven by their desire to depict reality in terms of their own personal experience rather than what was dictated by their elders who liked to copy older historical styles. Thus these young artists called themselves the Secessionists because they saw themselves as agitators against everything that was traditional and established. They joined together in the hopes of inventing a new artistic language that would define them.

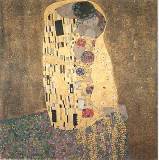

The leader of the Viennese Secessionists was Gustav Klimt, a painter who in his youth painted in the fashionable style of the period. As a painter, he became the bridge that helped clean the atmosphere and clear the ground for the more modern Viennese expressionists to take root. In The Kiss (1908), Klimt synthesizes the realistic portrayal of the lover's arms and faces with the abstract mosaic patterns of glowing colors borrowed from the more primitive, sensual Byzantine and Oriental artistic tradition. Likewise, in his later portraits of rich Viennese ladies, the representational elements are interwoven with abstract geometrical ornamentation that suggests the very modern handicrafts of the Secessionist movement. The end result of his portraiture is the destruction of the illusion of three dimensional space and the suggestion of a new form that is about to emerge in Paris, the collage.

The Kiss (1907)

Another major Viennese expressionist artist, Egon Schiele, came under the influence of Gustav Klimt, especially in the force of line, lack of space, and concern with symbolism. However, their similarities end there. Klimt is never involved in introspection and self-doubt because he emerges from the nineteenth-century optimism and joy rather than the apprehension, suspicion, and alienation of the twentieth-century. In Schiele's work we see the agony of life stripped to the bone, for his vision is one of suffering. Furthermore, he states his erotic fantasies without trying to mask them. Scheile tells us the devastating truth as he sees it, much as Freud explored and analyzed the psychological landscapes of his patients.

Self-portrait (1910)

It is also violence, pain and anxiety that Oscar Kokoschka, the leading Viennese expressionist, captures in his portraits. Like Schiele, Kokoschka's major concerns are hatred and destruction, conveyed through dynamic brushwork that captures the angularity and harshness of the forms. Both of these expressionist artists aimed at revealing their psychological insights and torment that each was feeling through portraiture. Their obsession with exposing the truth about emotional agony was the legacy that they had inherited from the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch, who saw illness as a metaphor for life. Through his melancholic paintings, Munch reveals how love drains the body of all sustenance until it withers into a death-like trance. Although not truly an expressionist, we see in him the beginning of a highly personalized interpretation of life that uses distortion in order to emphasize it.

Portrait of Old Man (1907)

In Paris, expressionism took on a different look because its formal and thematic concerns were not the same as Vienna's. Whereas the Viennese expressionists were concerned with revealing the hidden soul of a society that lived in denial of its collapsing values, the Paris expressionists fought to free artists from all prior formal restraints - rules, conventions, traditions - that limited the free use of color. Furthermore, whereas the Viennese expressionists' vision of the world is pessimistic and agonizing, the French expressionists concerned themselves with the joyful explosion of feeling of artists in love with the world that they lived in. The fauves, the name given to the French expressionists by a critic who likened them to wild beasts for their use of color and distortion, originated pure painting in that they rejected symbolic allusions as well as sentimental and intellectual preoccupations. Their obsession was the instinctive use of color harmony.

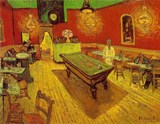

Night Café (1888)

The precursors of fauvism were Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, two nineteenth-century artists who experimented with two-dimensional planes, the dominant use of pure color, and highly textured brush strokes and who were fascinated by the art of primitive cultures. Van Gogh had been lead to become an artist through his love of the tangible world, of God and of mankind; Gauguin, on the other hand, through his love of sensuality. These two artists were so important to the fauves because they paved the way for artists to distance themselves from portraying what they saw realistically and to embrace painting as an interrelationship between brush strokes, colors, the relative scale of the parts and the combined effect of all elements. In short, Van Gogh and Gauguin contributed to modern painting through a legacy of vividness and visual pleasure. Henri Matisse, André Derain, Raoul Dufy, Maurice de Vlaminck and George Rouault continued this tradition.

Day of the Gods (1894)

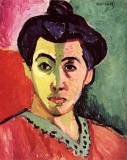

It was through vividness and visual pleasure that Henri Matisse wanted to revive painting. In his Madame Matisse: the Green Line (1905), the artist is not interested in capturing his wife in an academic, realistic manner, but rather, in conveying the keenness of his experience in all of its immediacy. How does he do this? For one, he does it through his choice of colors, and although glaring, he juxtaposes them in such a way as to make them appear to be harmonious. He paints the flesh next to the red background in cool tones, whereas the flesh next to the green is warm-toned. Her hair is blue with glimpses of bright red. Although the portrait seems to have been painted spontaneously in the spur of the moment, everything about it has been thought through. The colors support the brush strokes and the forms. In the end, we are left with a bold portrait of a handsome woman. Matisse would refer to his method as putting "order into my feelings." It is this love for order that can be seen in Harmony in Red (The Red Room), in which the distinction between art and nature are very unclear. The window frames the outside world as though it was a still life painting and the designs on the wallpaper and tablecloth, paradoxically, are teeming with life and vitality. Georges Rouault was another of the fauves. His artistic formation was due to his training to become a stained glass craftsman. When we look at his paintings, we are reminded of this fact by his use of color and light, his highly outlined figures and his religious imagery. Indeed, his paintings are renderings of stained glass windows as transformed by a painter. As one looks at them, it is almost as though each of the figures was being illuminated by a light that was shining through the canvas. Furthermore, each figure is highly simplified and confined by very harshly drawn black outlines. The ultimate effect is one of spirituality.

Madame Matisse (1905)

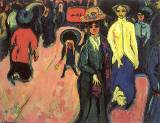

Still a different kind of expressionism sprung up in the German city of Dresden in 1905 - Die Brücke (The Bridge), composed of four architecture students: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. They chose painting over architecture because it offered them the opportunity to preserve the freshness, naiveté, and honesty of their sensations and visions. This they meant to do by capturing the essence of their subjects through the use of form and color, especially through angularity of line. Thus, the essential component of their art was spontaneity of expression. Their principal subjects were nudes in interiors and exteriors, the circus, street life and the music hall.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner was the leader of the Die Brücke, and he had a great talent for getting at the heart of the matter. He took his subjects from the world around him, urban landscapes and portraits of himself and his companions. In Street (1907), Kirchner captures the rhythm of women aimlessly scuttling about the city. He uses color to express the anxiety of city life: the sidewalk is pink, the faces are nauseous green. Similarly, he uses his feathery, cross-hatches to suggest the nervousness of city life. In his Self-Portrait with Model (1910), loud colors are juxtaposed (orange and blue, pink and green) and interrupted by contradictory colors (the pale color of the sitter's underwear, the lilac of his lips, the green strokes of both of their faces). Like Matisse's paintings, this one also suggests that it has been painted very energetically rather than carefully. Symbolically, Kirchner portrays himself holding a broad brush.

Dresden Street (1907)

The artist's associated with the Die Brücke loved to study the art of more primitive cultures for its use of distortion, color, and formal vitality. Max Pechstein's Indian and Woman presents the viewer with models who are obviously from a more primitive culture. The man is dressed in an indigenous costume of rich, bold colors and the woman is portrayed in the nude. Both are made to appear as if they were portrayed in the style of the Pacific. Erich Heckel's painting show a violent brushwork, but the paint is thinner and doesn't cover the whole surface of the canvas, creating the sense that it was done spontaneously and in haste. His Glassy Day (1913) suggests Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. Karl Schmidt-Rotluff's The Rising Moon reminds us of a young child's landscape in its use of pure color and bold, rhythmic line. The paintings of Emil Nolde, The Last Supper and Jesus and the Little Children are a reflection of the piety in which he lived. His use of ecstatic color, brush stroke and form are a testament to what he feels in his heart and the primal energy that he sought in Jesus. He strips forms to simple elements and consolidates colors in large areas as a means of expressing his fundamental emotions.

Glassy Day (1913)

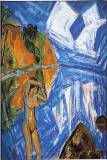

In nearby Munich, still another German expressionist group had sprung by 1911 - the Blaue Reiter. But although these two German groups were neighbors geographically, the Die Brücke's artistic concerns were very different from the Blaue Reiter's. For the Blaue Reiter, art needed to detach itself from the real, material world and become a spiritual, religious form of communication because art's primary function is to reveal the inner life of man. This spirituality can be pictorially represented through two different means: abstract compositions or a poetically expressive, rather than a strictly imitative, treatment of the visible world. But whereas the Die Brücke literally imitated primitive art, the Blaue Reiter extolled it not for its formal characteristics but, rather, because it was untainted by materialistic Western values. Thus for the Blaue Reiter, the primitives were true painters because they expressed themselves in a purely visual, pictorial way in order to convey internal truths.

Blue Horses (1911)

Franz Marc, one of the founders of the Blaue Reiter, was the first to see the use of color as a means of expressing emotion rather than of describing the material world of appearances. Marc's horses are painted in primary colors to suggest their sense of freedom and their harmonious relationship with the environment. He painted a horse as it felt about itself and as it sees the world. In Blue Horses, the horses blue color suggests freedom and the environment in which they live is rendered in primary colors. Stables fragments the bodies of horses to show the beauty of their forms, and its cubistic pictorial composition resembles the compartmentalizing that takes place in these quarters. The totally abstract Fighting Forms suggests the form, freedom and energy of horses rendered non-representationally. This is an example of pure painting devoid of the representative function. Unfortunately, Marc's life was cut short by World War I.

Picture with Archer (1909)

Untitled (1910)